Emma Minato

As a child I recall learning about healthy eating through Canada’s Food Guide. We listened to the teacher, looked at diagrams and probably did a little assignment before moving onto our next lesson. Outside of school I didn’t give the food guide much thought until a new version came out in 2019. I checked it out to see what was new, but I never paused to consider how interesting it may be to look at the past guides as well. That is until I stumbled across the first food guide and was immediately intrigued. I began to do some research and found the guides to be a fascinating reflection of nutritional goals and knowledge at different points in time.

As a child I recall learning about healthy eating through Canada’s Food Guide. We listened to the teacher, looked at diagrams and probably did a little assignment before moving onto our next lesson. Outside of school I didn’t give the food guide much thought until a new version came out in 2019. I checked it out to see what was new, but I never paused to consider how interesting it may be to look at the past guides as well. That is until I stumbled across the first food guide and was immediately intrigued. I began to do some research and found the guides to be a fascinating reflection of nutritional goals and knowledge at different points in time.

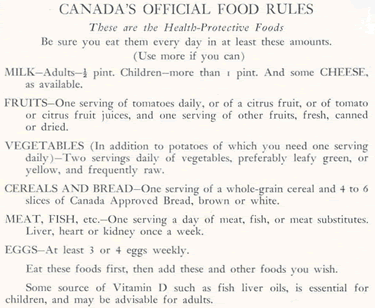

It all started in 1942, when the first food guide was released. At this time nutritional science was a newer field of study and Canadians were experiencing war-time rationing and poor nutrition. Vitamins had just been discovered in the 20s and new knowledge on nutrient deficiencies was causing concern. The general purpose of Canada’s Official Food Rules was to guide people to make healthy food choices and avoid malnutrition. Six food groups were identified: Milk; Fruit; Vegetables; Cereals and Breads; Meat, Fish, etc.; and Eggs. The rules stated a minimum of what should be eaten in a day, and specified that more should be eaten if possible. The first food guide recommended the following:

MILK- Adults- ½ pint. Children- more than 1 pint. And some cheese as available.

FRUITS- One serving of tomatoes daily, or of a citrus fruit, or of tomato or citrus fruit juices, and one serving of other fruits, fresh, canned or dried.

VEGETABLES- (In addition to potatoes of which you need one serving daily) – Two servings daily of vegetables, preferably leafy green or yellow and frequently raw.

CEREALS AND BREADS- one serving of a whole grain cereal and four to six slices of Canada Approved Bread, brown or white.

MEAT, FISH, etc. – One serving a day of meat, fish, or meat substitutes. Liver, heart or kidney once a week.

EGGS- at least 3 or 4 eggs weekly

Eat these foods first, then add these and other foods you wish.

Some source of vitamin D such as fish liver oils, is essential for children, and may be advisable for adults.

What had initially captured my interest to look into this topic was the recommendation from Canada’s Official Food Rules (1942) to eat four to six slices of Canada Approved Bread per day and so I decided to do a deeper dive into the reason behind this recommendation.

Why four to six slices of bread?

Bread has a rich history. It has been made for at least 14,000 years and has been a staple food item across the world. In the past, more bread was consumed than in the present day. In 1900 about 300 pounds of bread were eaten per capita in Canada. This decreased to 120 pounds by 1954, and to about 30 pounds in 2016. When the first Canadian food guide came out in 1942, not only was it common to eat more bread than in the present day, but the focus of healthy eating was on getting enough food and nutrients. While the recommendation to eat four to six slices of bread every day may sound like a lot, it makes sense within the context of the time.

What even is Canada Approved Bread?

Bread has evolved with advancements in technology. For most of its history, it was coarse and nutrient dense making it a healthy, staple food item. White flour was difficult and time consuming to produce, but with developments in technology it became more accessible and was popular by the early 1900s. Because white flour is much less nutrient dense, the United States and Great Britain began fortifying their bread with synthetic vitamins. Canadian nutritionists took a different route and aimed to utilize wheat’s natural vitamins with a long-extraction milling process. This method preserved some of the thiamine in the outer layers of the endosperm. Simply put, more good nutrients stayed in the bread. Flour that was made with this method was called Canada Approved Flour, which could then be made into Canada Approved Bread.

How exactly did they come to these recommendations?

The reasoning behind the recommendation for Canada Approved Bread is unclear and complex. The push for Canada Approved Bread was spearheaded by two Canadian ministries, Dr. Leonard H. Newman, and two nutritionists: Dr. Lionel B. Pett and Dr. Frederick Tisdale. One of the main reasons that Newman and his colleagues supported naturally fortified bread was because there wasn’t much research on synthetic vitamins at this time. They worried that synthetic vitamins could actually be harmful instead of helpful, especially if consumed in amounts that didn’t match natural vitamin intake. But, their persistent efforts to promote Canada Approved Bread was met with much opposition. Millers and bakers supported the use of synthetic vitamins. It was argued that synthetically fortified bread was quicker to produce which was important during war times and to prevent losing out on export sales. Despite Newman’s efforts, Canada Approved Bread did not gain traction and was removed from the food guide in 1949.

While it is fascinating to catch a glimpse of history, it is also interesting to see the progression to where we are now and to acknowledge how far we’ve come. Among other improvements, the current Canada’s Food Guide is much more inclusive. In 1992, the food guide first acknowledged that people’s energy needs and fuel intake can be different from one another based on factors such as age or activity level. Around the same time, the guide started to become more culturally inclusive as well. In 2007, the food guide was made available in twelve languages, including Cree, Ojibwe and Inuktitut. Indigenous partners have also been consulted to create a tailored food guide that acknowledges traditional foods. Of course there is still ongoing nutrition research and inclusivity goals, which makes me curious to see the next edition of Canada’s Food Guide.

Be sure to share on social media whatever you create and tag the Sidney Museum.

Facebook: @SidneyMuseum, Twitter: @SidneyMuseum, Instagram: @sidneymuseum

Recipe adapted from Carolyn Ekin’s recipe from her blog The 1940’s Experiment.

While we cannot bake Canada Approved Bread since they no longer make Canada Approved Flour, there are plenty of bread recipes from the 1940’s to try out. Many cookbooks contain at least one bread recipe and there are a number of recipes that have been posted on the internet.

Note: The original recipe called for old fashioned yeast, however Carolyn adapted the recipe for quick rise yeast since it is easier to find.

- 600 ml (2 ½ cups) of warm water

- 5 teaspoons of quick rise yeast

- couple pinches of sugar

- 2 lb (about 7 cups) of wholewheat (wholemeal) flour

- 1.5 teaspoons salt

- 1 tablespoon rolled oats (for top)

- spoonful of butter or margarine (or a drizzle of vegetable oil)

- Mix all dry ingredients in a large bowl except for the rolled oats.

- Add fat (or drizzle of vegetable oil). Pour in warm water and mix thoroughly.

- When dough comes together knead for 10 minutes until dough is silky.

- Place back in the bowl and cover. Let dough rise somewhere warm until doubled in size.

- Knead dough briefly again.

- Place dough into 4 x 1/2 lb tins (or 2 x 1 lb tins) that have been floured.

- Brush top with a little water and sprinkle on some rolled oats.

- Leave to rise for around 20 minutes.

- Place in the oven at 180 C (350 F) for around 30-40 mins (depending on the size of the loaf).

- Remove from the oven. Cool for at least 15 minutes before cutting.