A Historical and Contemporary Discussion on Politics and Women to Celebrate the 95th Anniversary of the Persons' Case

Presented by Charlotte Clar, Sidney Museum Outreach & Volunteer Coordinator on October 18, 2024, the 95th Anniversary of the Persons’ Case.

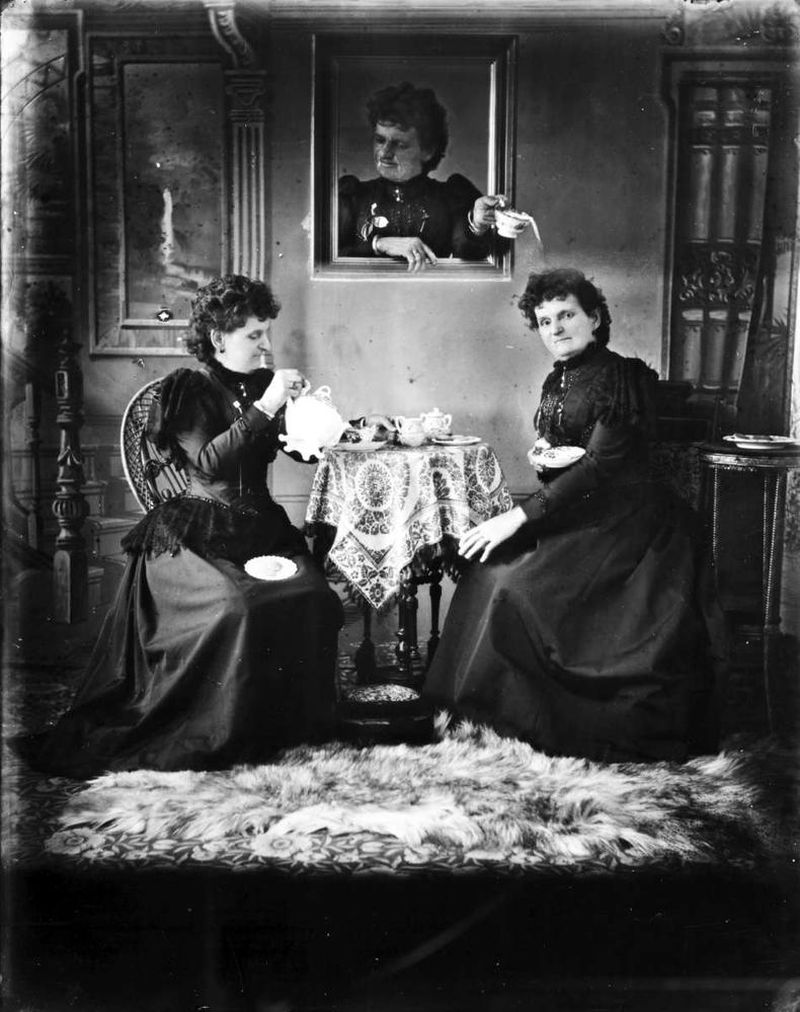

What is a Pink Tea?

When the Famous Five were campaigning for women to have the right to vote and the right to run for elected office, their suffrage meetings were disrupted by their opponents. Women traditionally held teas for special occasions and since men didn’t attend these teas, suffragists started calling their political meetings Pink Teas and very few opponents attended.

Image Source: Royal BC Museum / BC Archives, F-02852

Women's political participation in Canada

How many women have been involved in our country’s 157 year colonial government?

When doing research for this presentation, I was thinking about the Sidney Museum’s current exhibit Lost Liberties: The War Measures Act and how the War Measures Act was passed by the federal government. To me, this then begged the questions: How many women were involved in passing this act the three times it was done so in Canadian history and how many women have been involved in our country’s 157 year colonial government?

- The 12th Canadian Parliament of 1911-1917, that voted in the War Measures Act in 1914, was all men

- The 18th Parliament of 1936-1940 that voted in the War Measures Act again, had two women MPs: Agnes Campbell Macphail (1st elected female MP in 1921) and Martha Louise Black

- The 28th Parliament of 1968-1972 that voted in the War Measures Act in response to the 1970 October Crisis had one female MP, Winona Grace MacInnis

Only three women were ever involved with passing the War Measures Act that had severe consequences for tens of thousands of Canadians in the 20th century. It’s something interesting to think about as you go through the exhibit.

Shocking Statistics!

1844

Women were first recorded as voting in Canada in an election in Canada West.

1876

Canada’s first suffrage organization, Toronto Women’s Literary Club, was founded by Dr. Emily Stowe.

1895

47 male MPs voted in favour of women’s suffrage. The motion was defeated 104-47

1917

British Columbian women (except Asian and Indigenous women) won the rights to vote and to hold provincial office.

1917

Parliament passed the Wartime Elections Act. The right to vote federally was extended to women in the armed forces and female relatives of military men. However, Citizens considered of “enemy alien” birth and some pacifist communities are disenfranchised.

1918

Some women were granted Right to Vote in Federal Elections except those disenfranchised.

1940

Québec women became the last in Canada to earn the right to vote and run for office in provincial elections.

1947

Chinese and South Asian Canadians (but not Japanese) gained the right to vote federally and provincially.

1948

The federal Elections Act was changed so that race was no longer grounds for exclusion from voting in federal elections. Japanese Canadians became enfranchised the following year in 1949.

1949

Status Indians in British Columbia were granted the right to vote in provincial elections.

1960

Status Indians receive the right to vote in federal elections, no longer losing their status or treaty rights in the process.

1969

Status Indians receive the right to vote in Municipal elections in Quebec.

1988

The first Indigenous female MP was elected, Ethel Dorothy Blondin-Andrew, member of the Dene Nation.

1989

Audrey McLaughlin of the Yukon became the first woman to head a federal political party in North America.

1997

Nancy Karetak-Lindell became the first elected Inuit Female Member of Parliament for the new riding of Nunavut.

2007

The Premier of Québec appointed Canada’s first gender-balanced Cabinet.

What IS THE 'PERSONS' CASE?

In 1929, five women in Alberta won the judiciary battle to be recognized as person, therefore making them eligible for Senate appointments.

Who were the famous five?

The Famous Five were five female activists living in Alberta who came together to sign a petition asking the Supreme Court of Canada to recognize that the word ‘persons’ legally included women.

It is interesting to think about the ages of the Famous Five in 1927 when they started this campaign. These were women with decades of political activism experience behind them. Nellie McClung was the youngest at 54. Emily Murphy, Louise McKinney & Irene Parlby were all 59. Henrietta Muir Edwards was the oldest at 78.

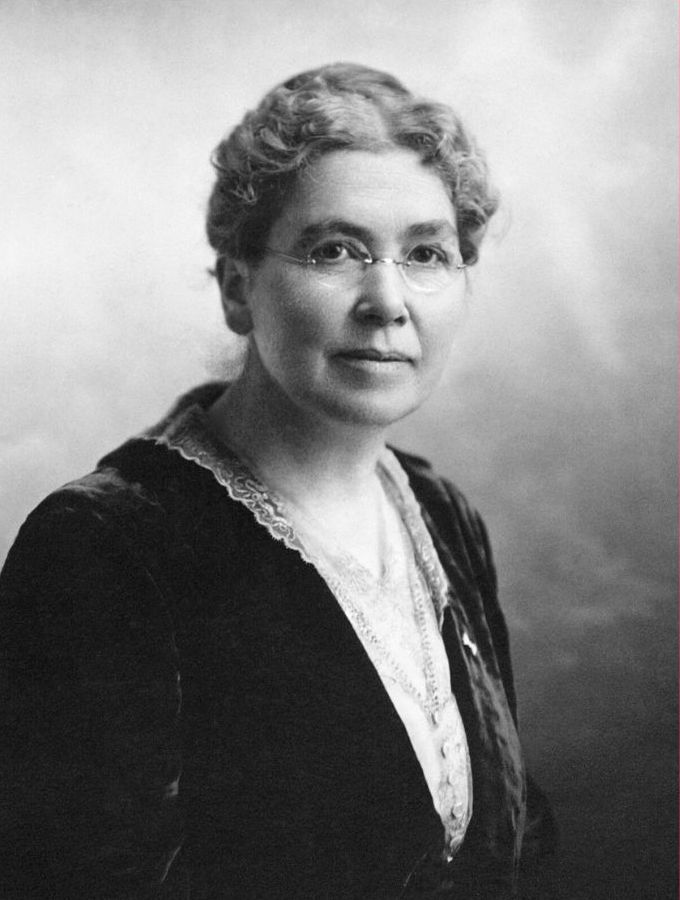

Emily Murphy

"Whenever I don't know where to fight or not, I fight."

Image Source: Provincial Archives of Alberta / Item A3355

Emily Gowan Ferguson was born on March 14, 1868 in Cookstown, Ontario to a family very much involved in political life and discussions. While attending private school in Toronto, she met Arthur Murphy whom she later married and had two daughters. In 1907 the family moved to Edmonton and Emily became an author, publishing four books under the pen name “Janey Canuck”, and involved in campaigns and organizations for women’s rights.

Emily was particularly interested in women’s property rights. In 1916, she helped persuade the Alberta legislature to pass the Dower Act that would allow a woman legal rights to one-third of her husband’s property.

Later that same year, Emily protested to the Attorney General about women not being allowed to attend the trial of several women in Edmonton who had been arrested as prostitutes. In response, the AG offered her a post of a police magistrate for Edmonton, and later Alberta.

It was Emily’s appointment as a magistrate that eventually led to the challenging of the definition of the word “persons” in the British North America Act (renamed the Constitution Act, 1867 in 1982). A lawyer asserted that she couldn’t be a judge as women were not included under the word “persons” in the eyes of the law. At the same time, a group of feminists in Alberta thought she should be appointed as Canada’s next Senator.

In 1927, Emily invited Nellie McClung, Irene Parlby, Henrietta Muir Edwards, and Louise McKinnney to her home where she had drafted a petition to put before the Supreme Court of Canada in a case that was named Edwards v. Attorney General of Canada. In their judgement on April 24, 1928, the Supreme Court denied the petition and so the “Famous Five” as they became known took their request to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London (Canada’s highest court of appeal until 1949) who reversed the decision on October 18, 1929.

Emily was never appointed as a Senator. Instead, that honour went to Cairine Wilson in 1930, only four months after the Privy Council verdict. Emily Murphy died on October 17, 1933.

Nellie McClung

"Never retract, never explain, never apologize, get the thing done and let them howl!"

Image Source: Library and Archives Canada / 3192002

Nellie Letitia Mooney was born on October 20, 1873 in Ontario but was raised on a homestead in Manitoba. Although she only started school at age 10, she completed a teaching certificate at 16 years old. She taught for 7 years until she married Robert McClung. The couple lived in Manitou, Manitoba, where Nellie became involved with the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and began writing which she continued to do throughout her life.

In 1911, the McClungs were living in Winnipeg with their five children where Nellie became involved in the women’s rights and reform movement. She was especially noted for her talent as an effective and humorous speaker. In 1914, she campaigned for women’s suffrage against the Conservative government and

staged a Mock Parliament to raise money and generate sympathy for the suffrage movement; she played the Premier.

The McClung’s then moved to Edmonton where Nellie continued to fight for suffrage, prohibition, and other reforms and went on speaking tours throughoutNorth America. In 1921 she was elected an MLA for Edmonton and served one term until 1926.

In 1927 she was approached by Emily Murphy, and joined the other “Famous Five” to submit a petition to the Supreme Court.

In 1933, the McClung’s moved to Saanich where Nellie continued to write and give public lectures. She also served on the CBC’s first Board of Governors and as a delegate to the League of Nations in 1938. Nellie McClung died on September 1, 1951.

Louise McKinney

"The purpose of a woman's life is just the same as the puropose of a man's life; that she may make the best possible contribution to the generation in which she is living."

Image Source: Glenbow Library and Archives / University of Calgary / CU1136168

Louise Crummy was born on September 22, 1868, in Frankville, Ontario to a Methodist family. She dreamed of being a doctor, but trained to be a teacher instead. She taught for 7 years in Ontario before moving to North Dakota to live with her sister. There, she became involved in the WCTU and met and married James McKinney, a fellow Ontarian temperance activist.

In 1903, the couple moved to a homestead near Claresholm, North-West Territories (later Alberta) where Louise established a branch of the WCTU, the first of forty chapters she would help open in less than a decade.

Louise was a popular public speaker who spoke about temperance and women’s enfranchisement. Eventually, she became president of the Alberta WCTU and vice-president of the federal organization for 22 years where she travelled to speak across North America and Europe. In 1916, partially due to her and her peer’s campaigning, Alberta passed a law prohibiting the sale of alcohol (at least, until 1923), and some women gained the right to vote.

In 1917, Louise became one of the first two women elected to a legislature in the British Empire when she was elected as an MLA in Alberta. (Roberta MacAdams also won a seat in the same election). Louise ran for office again in 1921, but lost.

Throughout her life Louise was also a lay preacher and Sunday school superintendent. She campaigned for women to become ministers in the Methodist and United Churches, but was unsuccessful.

After joining the other Famous Five for the Persons’ Case, Louise was appointed President of the Dominion WCTU in 1931 as well as the first World’s Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

Louise McKinney died on July 10, 1931.

Irene Parlby

"If politics mean...the effort to secure through legislative action better conditions of life for the people, greater opportunities for our children and other people's children...then it most assuredly is a woman's job as much as it is a man's job."

Image Source: United Farm Workers Historical Society Archives / UF 2005.0044.69 8

Mary Irene Marryat was born on January 9, 1868, in London, England where she was raised until her family moved to India when she was 13. Later she attended exclusive schools in Switzerland and Germany where she was interested in writing and theatre.

After travelling around Europe, she visited friends in Buffalo Lake, North-West Territories (later Alberta) where she met Water Parlby in 1896 and married one year later.

The couple moved to Alix, Alberta, where Irene enjoyed her farm life in rural Canada. They had one son.

In 1913, Irene was named secretary of the Alix Country Women’s Club where she helped establish a local library. That same year she also established the first women’s local of the United Farmers of Alberta of which she was President from 1916-1920. She was instrumental in transforming the group into an independent organization, the United Farm Women of Alberta. She advocated for better health care, social services, schools, and libraries for rural families.

In 1921, the United Farmers of Alberta transferred to become a political party and Irene was elected an MLA for her district in their majority government and appointed to the cabinet (the second woman in the British Empire after Mary Ellen Smith of BC who had only done so months before). She was named Minister without Portfolio, with special responsibility for advising the government on issues of particular concern to women and children, but without a budget or mandate to take any action. She became known as the “Women’s Minister” and was active on many issues including health care, improved wages for working women, and married women’s property rights. She was re-elected twice, serving a total of 14 years in the Legislature.

In 1930, Irene was appointed by the Prime Minister as one of three delegates to the League of Nations meeting in Switzerland.

Irene retired in 1935 to focus on her family, but still championed the betterment of women. That same year she became the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Alberta.

Irene Parlby died on July 12, 1965 at age 97.

Henrietta Muir Edwards

"If women had the vote there would be no need to come twice asking for better legislation for women and children."

Image Source: Glenbow Library and Archives / University of Calgary / CU1106662

Henrietta Louise Muir was born on December 18, 1849, in Montreal, Canada East, to a progressive evangelical family. She was home-schooled as well as went to private school, where she continuously encountered strong female role models.

In 1874, Henrietta and her sister Amelia established the Young Women’s Reading Room, a library and gathering place for

religious meetings and social events, as well as worked with the Working Girls Association, an organization to help women gain independence with affordable housing, training, and support, which she later became the director of and helped fund by selling her artwork.

Unable to go to art school because of her gender, Henrietta studied in New York City under a renowned portrait artist to become an accomplished artist herself. She painted portrait

miniatures of prominent figures such as Wilfrid Laurier (a personal friend). Her works were exhibited in Montreal, Ontario, and at the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts.

In 1876 she married Dr. Oliver Edwards. They couple would go on to have three children.

In 1878, she and her sister Amelia launched a magazine now considered the first Canadian magazine for working women, Woman’s Work in Canada. The publication employed only women and trained them to print the publication themselves. The sisters also established the Montreal Women’s Printing Office that same year. Sales from Henrietta’s artwork also helped fund the publication.

In 1883, the family moved to Indian Head, North-West Territories (now Saskatchewan) and Henrietta made time to study Canadian law informally, especially codes concerning women and children.

After her husband became ill in 1890, the family moved to Ottawa where Henrietta was appointed the governor of the National Council of Women of Canada’s law committee, a position she held for 30 years. She also wrote two legal handbooks for women and sought legal equality for Indigenous women.

In 1903, the family moved again, to Fort MacLeod, Alberta where Henrietta joined the WCTU and became involved in women’s suffrage.

In 1927, she joined the Famous Five to sign a petition for the Supreme Court of Canada. As Henrietta’s signature appeared first, the case was titled Edwards vs. Attorney General of Canada.

Henrietta Muir Edwards died on November 9, 1931.

Controversies

While thinking about what the Famous Five accomplished in their lifetimes, it is important to remember that in the modern day we do not always agree with all of their choices.

All of the Famous Five have been criticized as racist and elitist, specifically for their beliefs in sterilization and eugenics. They were supporters of Alberta’s Sexual Sterilization Act, in which the involuntary sterilization of thousands of women considered “psychotic” and “mentally deficient” took place from 1928-1972. A disproportionate number of them were Indigenous women.

Louise McKinney has been criticized for her views on stricter immigration laws to keep out unwanted, often racialized, individuals. She also lobbied for the creation of institutions for “mental defectives” – seen as a means to prevent istitutionalized persons from reproducing.

While she was a judge, Emily Murphy believed immigrants, particularly people who were Asian or Black, were responsible for the illicit drug trade and the harms it caused.

DISCUSSION

- How far have women’s rights progressed in the past 100+ years?

- Do you think women’s suffrage is being remembered in Canada?

- What is something you learned that struck you the most?